America's Child-Poverty Rate Has Hit a Record Low

It fell thanks to government policies, not the expansion of the economy, researchers found.

The economy is nearing full employment. The stock market is at record highs. The expansion keeps continuing. Add to that one more very good piece of economic news: The child-poverty rate fell to a record low in 2016.

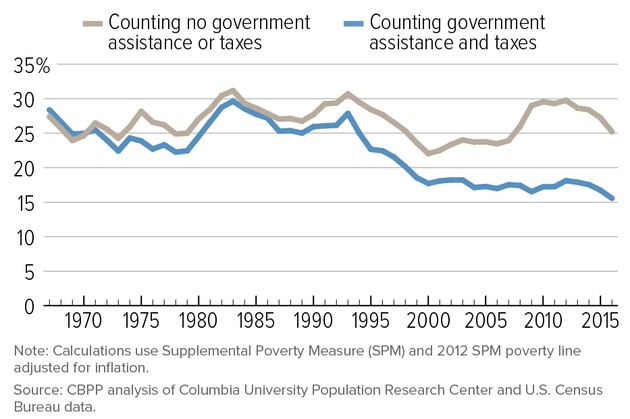

That finding comes from a new analysis of government and academic data by Isaac Shapiro and Danilo Trisi, both researchers at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan, Washington-based think tank. The child-poverty rate declined to 15.6 percent in 2016, the researchers found, down from a post-recession high of 18.1 percent in 2012 and from 28.4 percent in 1967. That means that roughly 11.5 million kids were living in households below the poverty threshold last year. “The figures were actually a little surprising to us, and might be surprising to those who are following the poverty debate,” said Shapiro. “The argument, at least on the conservative side, is that we have poured a lot of money into safety-net programs and poverty hasn’t gone down. But it has.”

The most recent drop in the child-poverty rate is due to a tighter labor market, the researchers found. More parents are back at work, with competition among employers starting to drive wages up even for very low-income workers. That has helped to push the overall poverty rate down to 12.7 percent. That said, the near-halving of the child-poverty rate over the past half-century is not primarily due to improvements in the economy. In fact, stagnating wages, reduced bargaining power, automation, and offshoring have held down the earnings of families in the bottom of the income spectrum, and spiraling income inequality has meant that most of the gains of economic growth have gone to families at the top. Instead, it is the expansion of the safety net—in particular through the food-stamp program and provisions like the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit—that has been most responsible for moving millions of kids above the poverty line over time, the researchers found.

The expansion of the economy alone has done little to push down the child-poverty rate. Not taking government benefits and tax policies into account, the rate has barely budged since the late 1960s, going from 27.4 percent in 1967 to 25.1 percent in 2016. But after accounting for government benefits and tax credits, it has dropped to its all-time low. All in all, the government’s policies moved 38 percent of kids who would otherwise be poor above the poverty line in 2016, the report estimated. “It’s striking to see how much the strength of the safety net has increased over time,” Trisi said. “That’s very good news.”

Despite the recent decline, the United States still has a far higher child-poverty rate than other high-income countries, with devastating short- and long-term effects. When children grow up in impoverished households—a particular concern for children of color, whose poverty rate is triple that of white children—it does not just mean worse grades, missed days of school, and skipped meals, researchers have found. It has profound, long-term effects, in terms of health, educational achievement, earnings, and even mortality.

According to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the United States’ child-poverty rate is significantly higher than that in 30 other industrialized economies, including Poland, Mexico, and Estonia, as well as countries like Japan, Germany, and France. “Child poverty remains far too high in this country, particularly given how wealthy our country is,” Shapiro said. “It’s still higher than in other, comparably wealthy countries. And even though government programs have expanded, we still do far less to reduce child poverty than other nations.” Many European countries, for instance, pay cash allowances to lower-income families with young children.

The new child-poverty figures come as bipartisan support is building for an expansion of the Child Tax Credit, an expansion that could potentially reduce the child-poverty rate even further. The credit, established during the Clinton presidency, is currently worth as much as $1,000 per child. The Republican Senators Mike Lee of Utah and Marco Rubio of Florida have led a push to increase that sum significantly, a policy initiative Democrats have broadly supported. This month, a prominent group of conservative think tanks and scholars—among them Ramesh Ponnuru of the National Review, the Family Research Council, and the Niskanen Center— launched a campaign to increase the size of the credit as well.

The Republican tax framework released with fanfare last week did contain some language gesturing towards a larger Child Tax Credit. But the plan might not end up helping low-income families with kids, due to the way the credits, exemptions, and deductions in the plan are structured. “Unfortunately, the Big Six wouldn’t reduce child poverty at all, and in the long run would probably increase child poverty,” Shapiro said, because low-income programs would likely be cut to pay for the regressive tax cuts in the proposal.

But Lee and Rubio, among other Republicans, are pushing to ensure that a major expansion of the Child Tax Credit makes it into any tax-reform bill. “Given the fundamental reforms of the framework, the child credit must be at least doubled in order to ensure working families get real tax relief,” the two senators said in a statement. “The child credit should also be applied to payroll tax liability in order to cut the taxes that working class families pay.”

Democrats have also pushed for expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit, which buoys the earnings of millions of low-wage families and, along with the Child Tax Credit, lifted 5 million kids out of poverty in 2016. That said, the tax policy does not support parents without earned income, leaving an estimated 1.5 million American households with close to no cash income, home to as many as 3 million children.

The CBPP researchers measured child poverty according to the so-called “anchored supplemental poverty measure.” Unlike the overall poverty rate released by the Census, this measure takes into account non-cash benefits, like food stamps, as well as tax benefits, like the Child Tax Credit. It also takes into account things like out-of-pocket medical spending, and therefore gives a much better picture of the true poverty rate, the researchers argue.

In the analysis, a family with two children and two adults living in rental housing in an average-cost area had to have less than $26,200 in annual disposable income to fall below the poverty threshold. The typical such family living under the poverty line had earnings of just $15,000, with the majority receiving help from the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Child Tax Credit, and the school lunch program, and roughly half receiving food stamps.

Ultimately, a better economy might help bring the rate down, the researchers found. But it will take government policies to move the number to zero.