Geronimo

Geronimo | |

|---|---|

| Goyaałé | |

Photograph by Frank Rinehart, 1898 | |

| Bedonkohe Apache leader | |

| Preceded by | Juh |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 16, 1829 No-doyohn Cañon, Arizona[1] |

| Died | February 17, 1909 (aged 79) Fort Sill, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Resting place | Apache Indian Prisoner of War Cemetery, Fort Sill 34°41′49″N 98°22′13″W / 34.696814°N 98.370387°W, |

| Spouse(s) | Alope, Ta-ayz-slath, Chee-hash-kish, Nana-tha-thtith, Zi-yeh, She-gha, Shtsha-she, Ih-tedda, and Azul |

| Children | Chappo, Dohn-say |

| Mother tongue | Apache, Spanish |

| Signature | |

|

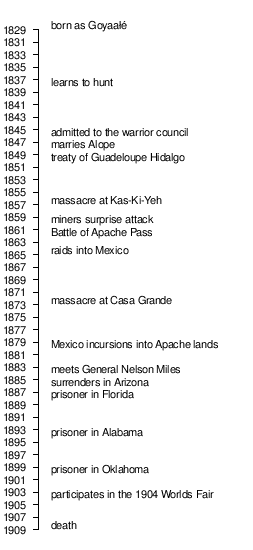

Geronimo's chronology |

|

Geronimo (Mescalero-Chiricahua: Goyaałé, Athapascan pronunciation: [kòjàːɬɛ́], lit. 'the one who yawns'; June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) was a military leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people. From 1850 to 1886, Geronimo joined with members of three other Central Apache bands – the Tchihende, the Tsokanende (called Chiricahua by Americans) and the Nednhi – to carry out numerous raids, as well as fight against Mexican and U.S. military campaigns in the northern Mexico states of Chihuahua and Sonora and in the southwestern American territories of New Mexico and Arizona.

Geronimo's raids and related combat actions were a part of the prolonged period of the Apache–United States conflict, which started with the Americans continuing to take land, including Apache lands, following the end of the war with Mexico in 1848. Reservation life was confining to the free-moving Apache people, and they resented restrictions on their customary way of life.[2] Geronimo led breakouts from the reservations in attempts to return his people to their previous nomadic lifestyle. During Geronimo's final period of conflict from 1876 to 1886, he surrendered three times and eventually accepted life on the Apache reservations. While well-known, Geronimo was not a chief of the Bedonkohe band of the Central Apache but a shaman, as was Nokay-doklini among the Western Apache.[3][4] However, since he was a superb leader in raiding and warfare, he frequently led large numbers of 30 to 50 Apache men.[4]

In 1886, after an intense pursuit in northern Mexico by American forces that followed Geronimo's third 1885 reservation breakout, Geronimo surrendered for the last time to Lt. Charles Bare Gatewood. Geronimo and 27 other Apaches were later sent to join the rest of the Chiricahua tribe, which had been previously exiled to Florida.[5] While holding him as a prisoner, the United States capitalized on Geronimo’s fame among non-Indians by displaying him at various fairs and exhibitions. In 1898, for example, Geronimo was exhibited at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska; seven years later, the Indian Office provided Geronimo for use in a parade at the second inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt. He died at the Fort Sill hospital in 1909, as a prisoner of war, and was buried at the Fort Sill Indian Agency Cemetery, among the graves of relatives and other Apache prisoners of war.

Background[edit]

Apache is the collective term for several culturally related groups of Native Americans resident in the Southwest United States. The current division of Apachean groups includes the Western Apache, Chiricahua, Mescalero, Jicarilla, Lipan and Plains Apache (formerly Kiowa-Apache). The first Apache raids on Sonora and Chihuahua took place in the late 17th century. To counter the early Apache raids on Spanish settlements, presidios were established at Janos (1685) in Chihuahua and at Fronteras (1690) in what is now northeastern Sonora, then Opata country. In 1835, Mexico had placed a bounty on Apache scalps. Two years later, Mangas Coloradas became principal chief and war leader and began a series of raids against the Mexicans. Apache raids on Mexican villages were so numerous and brutal that no area was safe.[6] Between 1820 and 1835 alone, some 5,000 Mexicans died in Apache raids, and 100 settlements were destroyed.[7]

During the decades of Apache-Mexican and Apache-United States conflicts, raiding had become embedded in the Apache way of life, used for strategic purposes as well as economic enterprise.[8] Speaking of the start of the Spanish/Mexican Apache conflict, Debo states, "Thus the Apaches were driven into the mountains and raiding the settled communities became a way of life for them, an economic enterprise as legitimate as gathering berries or hunting deer..." and often there was overlap between raids for economic need and warfare.[9] Raids ranged from stealing livestock and other plunder, to the capture and/or killing of victims, sometimes by torture.[10] Mexicans and Americans responded with retaliatory attacks against the Apache which were no less violent and were very seldom limited to identified individual adult enemies, much like the Apache raids. The raiding and retaliation fed the fires of a virulent revenge warfare that reverberated back and forth between Apaches and Mexicans and later, Apaches and Americans. From 1850 to 1886, Geronimo, as well as other Apache leaders, conducted attacks, but Geronimo was driven by a desire to take revenge for the murder of his family by Mexican soldiers and accumulated a record of brutality during this time that was unmatched by any of his contemporaries.[11] His fighting ability extending over 30 years forms a major characteristic of his persona.[9]

Within Geronimo's own Chiricahua tribe, many had mixed feelings about him. While respected as a skilled and effective leader of raids or warfare, he emerges as not very likable, and he was not widely popular among the other Apaches.[4] This was primarily because he refused to give in to American government demands, causing some Apaches to fear the American response. Nevertheless, the Apache people stood in awe of Geronimo's powers, which he demonstrated to them on a series of occasions. These powers indicated to other Apaches that Geronimo had supernatural gifts that he could use for good or ill. In eyewitness accounts by other Apaches, Geronimo was able to become aware of distant events as they happened,[12] and he was able to anticipate future events.[13] He also demonstrated powers to heal other Apaches.[14]

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

This article appears to contradict itself on whether he was born in Arizpe as said in the infobox or by the river. The reference given is the same.. (February 2023) |

Geronimo was born to the Bedonkohe band of the Apache near Turkey Creek, a tributary of the Gila River in the modern-day state of New Mexico, then part of Mexico, though the Apache disputed Mexico's claim.[1] His grandfather, Mahko, had been chief of the Bedonkohe Apache. He had three brothers and four sisters.[15]

His parents raised him according to Apache traditions. After the death of his father, his mother took him to live with the Tchihende, and he grew up with them. Geronimo married a woman named Alope, from the Nedni-Chiricahua band of Apache, when he was 17; they had three children. She was the first of nine wives.[citation needed]

Massacre at Janos[edit]

On March 5, 1851, a company of 400 Mexican soldiers from Sonora led by Colonel José María Carrasco attacked Geronimo's camp outside Janos (Kas-Ki-Yeh in Apache) while the men were in town trading.[16][17] Carrasco claimed he had followed the Apaches to Janos, Chihuahua, after they had conducted a raid in Sonora, taken livestock and other plunder and badly defeated Mexican militia.[18][19] Among those killed in Carrasco's attack were Geronimo's wife, children and mother.[20][21] The loss of his family led Geronimo to hate all Mexicans for the rest of his life; he and his followers would frequently attack and kill any group of Mexicans that they encountered.[9] Throughout Geronimo's adult life his antipathy toward, suspicion of, and dislike for Mexicans was demonstrably greater than for Americans.[22]

Recalling that at the time his band was at peace with the Mexicans, Geronimo remembered the incident as follows:

Late one afternoon when returning from town we were met by a few women and children who told us that Mexican troops from some other town had attacked our camp, killed all the warriors of the guard, captured all our ponies, secured our arms, destroyed our supplies, and killed many of our women and children. Quickly we separated, concealing ourselves as best we could until nightfall, when we assembled at our appointed place of rendezvous – a thicket by the river. Silently we stole in one by one, sentinels were placed, and when all were counted, I found that my aged mother, my young wife, and my three small children were among the slain.[23]

War with Mexico[edit]

Geronimo's chief, Mangas Coloradas (Spanish for "red sleeves"), sent him to Cochise's band for help in his revenge against the Mexicans.[24] It was during this incident that the name Geronimo came about. This appellation stemmed from a battle in which, ignoring a deadly hail of bullets, he repeatedly attacked Mexican soldiers with a knife. The origin of the name is a source of controversy with historians, some writing that it was appeals by the soldiers to Saint Jerome ("Jerónimo!") for help. Debo repeats this, speculating also an alternative unlikely in terms of phonetics, that it may have been "as close as they [Mexican soldiers] could come to the choking sounds that composed his name."[25]

Attacks and counterattacks with Mexicans were common. In December 1860, 30 miners began a surprise attack on an encampment of Bedonkohes Apaches on the west bank of the Mimbres River. According to historian Edwin R. Sweeney, the miners "... killed four Indians, wounded others, and captured thirteen women and children." Attacks by the Apache again followed, with raids against U.S. citizens and property.[26]

In 1873 the Mexicans once again attacked the Apache.[27] After months of fighting in the mountains, the Apaches and Mexicans decided on a peace treaty at Casas Grandes.[27] After terms were agreed, the Mexican troops gave mezcal to the Apaches, and while they were intoxicated, they attacked and killed 20 Apaches and captured some.[27] The Apache were forced to retreat into the mountains once again.[27]

I have killed many Mexicans; I do not know how many, for frequently I did not count them. Some of them were not worth counting. It has been a long time since then, but still I have no love for the Mexicans. With me they were always treacherous and malicious.

My Life: The Autobiography of Geronimo, 1905.

Though outnumbered, Geronimo fought against both Mexican and United States troops and became famous for his daring exploits and numerous escapes from incarceration from 1858 to 1886.[28] One such escape, as legend has it, took place in the Robledo Mountains of southwest New Mexico. The legend states that Geronimo and his followers entered a cave, and the U.S. soldiers waited outside the entrance for him, but he never came out. Later, it was heard that Geronimo was spotted outside, nearby. The second entrance through which he escaped has yet to be found, and the cave is called Geronimo's Cave, even though no reference to this event or this cave has been found in the historic or oral record. Moreover, there are many stories of this type with other caves referenced that state that Geronimo or other Apaches entered to escape troops but were not seen exiting. These stories are in all likelihood apocryphal.[26]

Geronimo campaign[edit]

The Apache–United States conflict was a direct outgrowth of the much older Apache–Mexican conflict which had been ongoing in the same general area since the beginning of Mexican/Spanish settlement during the 17th century.

While Apaches were shielded from the violence of warfare on the reservation, disability and death from diseases like malaria were much more prevalent.[29] On the other hand, rations were provided by the government, though at times the corruption of Indian agents caused rationing to become perilously scarce.[30] The people, who had lived as semi-nomads for generations, disliked the restrictive reservation system. Rebelling against reservation life, other Apache leaders had led their bands in "breakouts" from the reservations.[citation needed]

On three occasions – April or August 1878;[31][32] September 1881;[33] and May 1885[34][35] – Geronimo led his band of followers in breakouts from the reservation to return to their former nomadic life associated with raiding and warfare.[4] Following each breakout, Geronimo and his band would flee across Arizona and New Mexico to Mexico, killing and plundering as they went, and establish a new base in the rugged and remote Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains.[14] In Mexico, they were insulated from pursuit by U.S. armed forces. The Apache knew the rough terrain of the Sierras intimately,[36] which helped them elude pursuit and protected them from attack. The Sierra Madre mountains lie on the border between the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua, which allowed the Apache access to raid and plunder the small villages, haciendas, wagon trains, worker camps and travelers in both states.[36] From Mexico, Apache bands also staged surprise raids back into the United States, often seeking to replenish their supply of guns and ammunition. Utley refers to a specific raid in March 1883, in which Geronimo's people split up with Geronimo and Chihuahua raiding in the Sonora River valley to collect livestock and provisions, while Chatto and Bonito raided through southern Arizona to gather weapons and cartridges.[37] In these raids into the United States, the Apaches moved swiftly and attacked isolated ranches, wagon trains, prospectors and travelers. They often killed all the persons they encountered in order to avoid detection and pursuit as long as possible before they slipped back over the border into Mexico.[37]

The "breakouts" and the subsequent resumption of Apache raiding and warfare caused the Mexican Army and militia as well as United States forces to pursue and attempt to kill or apprehend off-reservation "renegade" Apache bands, including Geronimo's, wherever they could be found. Because the Mexican army and militia units of Sonora and Chihuahua were unable to suppress the several Chiricahua bands based in the Sierra Madre mountains, in 1883 Mexico allowed the United States to send troops into Mexico to continue their pursuit of Geronimo's band and the bands of other Apache leaders.[38]

The Indians always tried to live peaceably with the white soldiers and settlers. One day during the time that the soldiers were stationed at Apache Pass I made a treaty with the post. This was done by shaking hands and promising to be brothers. Cochise and Mangus-Colorado did likewise. I do not know the name of the officer in command, but this was the first regiment that ever came to Apache Pass. This treaty was made about a year before we were attacked in a tent, as above related. In a few days after the attack at Apache Pass we organized in the mountains and returned to fight the soldiers.

Geronimo's Story of His Life, Coming of the White Men, 1909.

General Crook said to me, "Why did you leave the reservation?" I said: "You told me that I might live in the reservation the same as white people lived. One year I raised a crop of corn, and gathered and stored it, and the next year I put in a crop of oats, and when the crop was almost ready to harvest, you told your soldiers to put me in prison, and if I resisted, to kill me. If I had been let alone I would now have been in good circumstances, but instead of that you and the Mexicans are hunting me with soldiers.

Geronimo's Story of His Life, in Prison and on the War Path, 1909.

On May 17, 1885, a number of Apache including Nana, Mangus (son of Mangas Coloradas), Chihuahua, Naiche, Geronimo, and their followers fled the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona after a show of force against the reservation's commanding officer Britton Davis. Department of Arizona General George Crook dispatched two columns of troops into Mexico, the first commanded by Captain Emmet Crawford and the second by Captain Wirt Davis. Each was composed of a troop of cavalry (usually about forty men) and about 100 Apache Scouts recruited from among the Apache people.[39] These Apache units proved effective in finding the mountain strongholds of the Apache bands and killing or capturing them.[40] It was highly unsettling for Geronimo's band to realize their own tribesmen had helped find their hiding places.[41] They pursued the Apache through the summer and autumn through Mexican Chihuahua and back across the border into the United States. The Apache continually raided settlements, murdering other innocent Native Americans and civilians and stealing horses.[42] Over time this persistent pursuit by both Mexican and American forces discouraged Geronimo and other similar Apache leaders, and caused a steady and irreplaceable attrition of the members of their bands, which taken all together eroded their will to resist and led to their ultimate capitulation.

Crook was under increased pressure from the government in Washington. He launched a second expedition into Mexico, and on January 9, 1886, Crawford located Geronimo and his band. His Apache Scouts attacked the next morning and captured the Apache's herd of horses and their camp equipment. The Apaches were demoralized and agreed to negotiate for surrender. Before the negotiations could be concluded, Mexican troops arrived and mistook the Apache Scouts for the enemy Apache. The Mexican government had accused the scouts of taking advantage of their position to conduct theft, robbery, and murder in Mexico.[43] They attacked and killed Captain Crawford. Lt. Maus, the senior officer, met with Geronimo, who agreed to meet with General Crook. Geronimo named as the meeting place the Cañon de los Embudos (Canyon of the Funnels), in the Sierra Madre Mountains about 86 miles (138 km) from Fort Bowie and about 20 miles (32 km) south of the international border, near the Sonora/Chihuahua border.[42]

During the three days of negotiations in March 1886, photographer C. S. Fly took about 15 exposures of the Apache on 8 by 10 inches (200 by 250 mm) glass negatives.[45] One of the pictures of Geronimo with two of his sons standing alongside was made at Geronimo's request. Fly's images are the only existing photographs of Geronimo's surrender.[44] His photos of Geronimo and the other free Apaches, taken on March 25 and 26, are the only known photographs taken of an American Indian while still at war with the United States.[44] Among the Indians was a white boy Jimmy McKinn, also photographed by Fly, who had been abducted from his ranch in New Mexico in September 1885.[citation needed]

Geronimo, camped on the Mexican side of the border, agreed to Crook's surrender terms. That night, a soldier who sold them whiskey said that his band would be murdered as soon as they crossed the border. Geronimo, Nachite, and 39 of his followers slipped away during the night. Crook exchanged a series of heated telegrams with General Philip Sheridan defending his men's actions, until on April 1, 1886, when he sent a telegram asking Sheridan to relieve him of command, to which Sheridan agreed.[45]

Sheridan replaced Crook with General Nelson A. Miles. In 1886, Miles selected Captain Henry Lawton to command B Troop, 4th Cavalry, at Fort Huachuca, and First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood, to lead the expedition that brought Geronimo and his followers back to the reservation system for a final time.[46] Lawton was given orders to head up actions south of the U.S.–Mexico boundary, where it was thought that Geronimo and a small band of his followers would take refuge from U.S. authorities.[46] Lawton was to pursue, subdue, and return Geronimo, dead or alive, to the United States.[46]

Lawton's official report dated September 9, 1886, sums up the actions of his unit and gives credit to a number of his troops for their efforts. Geronimo gave Gatewood credit for his decision to surrender as Gatewood was well known to Geronimo, spoke some Apache, and was familiar with and honored their traditions and values. He acknowledged Lawton's tenacity for wearing the Apaches down with constant pursuit. Geronimo and his followers had little or no time to rest or stay in one place. Completely worn out, the small band of Apaches returned to the U.S. with Lawton and officially surrendered to General Miles on September 4, 1886, at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona.[24][46]

When Geronimo surrendered, he had in his possession a Winchester Model 1876 lever-action rifle with a silver-washed barrel and receiver, bearing Serial Number 109450. It is on display at the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York. Additionally, he had a Colt Single Action Army revolver with a nickel finish and ivory stocks bearing Serial Number 89524, and a Sheffield Bowie knife with a dagger type blade and a stag handle made by George Wostenholm in an elaborate silver-studded holster and cartridge belt. The revolver, rig, and knife are on display at the Fort Sill museum.[26][47]

The debate remains as to whether Geronimo surrendered unconditionally. He repeatedly insisted in his memoirs that his people who surrendered had been misled, and that his surrender as a war prisoner in front of uncontested witnesses (especially General Stanley) was conditional. General Oliver O. Howard, chief of US Army Division of the Pacific, said on his part that Geronimo's surrender was accepted as that of a dangerous outlaw without condition. Howard's account was contested in front of the US Senate.[citation needed]

According to National Geographic, "the governor of Sonora claimed in 1886 that in the last five months of Geronimo's wild career, his band of 16 warriors slaughtered some 500 to 600 Mexicans."[48][49] At the end of his military career, he led a small band of 38 men, women and children. They evaded thousands of Mexican and American troops for more than a year, making him the most famous Native American of the time and earning him the title of the "worst Indian who ever lived" among white settlers.[50] According to James L. Haley, "About two weeks after the escape there was a report of a family massacred near Silver City; one girl was taken alive and hanged from a meat hook jammed under the base of her skull."[51] His band was one of the last major forces of independent Native American warriors who refused to accept the United States occupation of the American West.[citation needed]

Prisoner of war[edit]

Geronimo and other Apaches, including the Apache Scouts who had helped the Army track him down, were sent as prisoners to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. The Army held them there for about six weeks before they were sent to Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida, and his family was sent to Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos) in St. Augustine, Florida.[52] This prompt action prevented the Arizona civil authorities from intervening to arrest and try Geronimo for the death of the many Americans who had been killed during the previous decades of raiding.[53][54]

"In that alien climate," The Washington Post reported, "the Apache died 'like flies at frost time.' Businessmen there soon had the idea to have Geronimo serve as a tourist attraction, and hundreds of visitors daily were let into the fort to lay eyes on the 'bloodthirsty' Indian in his cell."[55] While the prisoners of war were in Florida, the government relocated hundreds of their children from their Arizona reservation to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. More than a third of the students quickly perished from tuberculosis, "died as though smitten with the plague", the Post reported.[55]

The Chiricahuas remained at Fort Pickens until 1888 when they were relocated to Mt. Vernon Barracks in Alabama,[56] where they were reunited with their families. After 1/4 of the population died of tuberculosis,[55] the Chiricahuas, including Geronimo, were relocated to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in 1894; they built villages scattered around the post based on kindred groups.[57] Geronimo, like other Apaches, was given a plot of land on which he took up farming activities.[58] On the train ride to Fort Sill, many tourists wanted a memento of Geronimo, so they paid 25 cents for a button that he cut off his shirt or a hat he took off his head. As the train would pull into depots along the way, Geronimo would buy more buttons to sew on and more hats to sell.[59]

In 1898 Geronimo was part of a Chiricahua delegation from Fort Sill to the Trans-Mississippi International Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska. Previous newspaper accounts of the Apache Wars had impressed the public with Geronimo's name and exploits, and in Omaha he became a major attraction. The Omaha Exposition gave Geronimo celebrity status, and for the rest of his life he was in demand as an attraction in fairs large and small. The two largest were the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo, New York, in 1901, and the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Under Army guard, Geronimo dressed in traditional clothing and posed for photographs and sold his crafts.[60]

After the fair, Pawnee Bill’s Wild West shows brokered an agreement with the government to have Geronimo join the show, again under Army guard. The Indians in Pawnee Bill’s shows were depicted as "lying, thieving, treacherous, murderous" monsters who had killed hundreds of men, women and children and would think nothing of taking a scalp from any member of the audience, given the chance. Visitors came to see how the "savage" had been "tamed," and they paid Geronimo to take a button from the coat of the vicious Apache "chief." (Geronimo was not a chief.) The shows put a good deal of money in his pockets and allowed him to travel though never without government guards.[55]

In President Theodore Roosevelt's 1905 Inaugural Parade, Geronimo rode horseback down Pennsylvania Avenue with five Indian chiefs who wore full headgear and painted faces.[61] The intent, one newspaper stated, was to show Americans "that they have buried the hatchet forever."[55] They created a sensation and brought the crowds to their feet along the parade route.[62] Later that same week Geronimo met with Roosevelt and made a request for the Chiricahuas at Fort Sill to be relieved of their status as prisoners of war and allowed to return to their homeland in Arizona. President Roosevelt refused, referring to the continuing animosity in Arizona for the deaths of civilian men, women, and children associated with Geronimo's raids during the prolonged Apache Wars.[63][64] Through an interpreter, Roosevelt told Geronimo that the Indian had a "bad heart". "You killed many of my people; you burned villages…and were not good Indians." Roosevelt responded that he would "see how you and your people act" on the reservation.[55]

In 1905, Geronimo agreed to tell his story to S. M. Barrett, Superintendent of Education in Lawton, Oklahoma. Barrett had to appeal to President Roosevelt to gain permission to publish the book. Geronimo came to each interview knowing exactly what he wanted to say. He refused to answer questions or alter his narrative. He expressed himself in Spanish.[65] Barrett did not seem to take many liberties with Geronimo's story as translated into English by Asa Daklugie. Frederick Turner re-edited this autobiography by removing some of Barrett's footnotes and writing an introduction for the non-Apache readers. Turner notes the book is in the style of an Apache reciting part of his oral history.[66][failed verification]

When I was at first asked to attend the St. Louis World's Fair I did not wish to go. Later, when I was told that I would receive good attention and protection, and that the President of the United States said that it would be all right, I consented ... Every Sunday the President of the Fair sent for me to go to a wild west show. I took part in the roping contests before the audience. There were many other Indian tribes there, and strange people of whom I had never heard ... I am glad I went to the Fair. I saw many interesting things and learned much of the white people. They are a very kind and peaceful people. During all the time I was at the Fair no one tried to harm me in any way. Had this been among the Mexicans I am sure I should have been compelled to defend myself often.[67]

Later that year, the Indian Office took him to Texas, where he shot a buffalo in a roundup staged by 101 Ranch Real Wild West for the National Editorial Association. Geronimo was escorted to the event by soldiers, as he was still a prisoner. The teachers who witnessed the staged buffalo hunt were unaware that Geronimo’s people were not buffalo hunters.[citation needed]

Death[edit]

In February 1909, Geronimo was thrown from his horse while riding home and lay in the cold all night until a friend found him extremely ill.[50] He died of pneumonia on February 17, 1909, as a prisoner of the United States at Fort Sill.[68] On his deathbed, he confessed to his nephew that he regretted his decision to surrender.[50] His last words were reported to be said to his nephew, "I should have never surrendered. I should have fought until I was the last man alive."[69] He was buried at Fort Sill in the Beef Creek Apache Cemetery.[70]

Family[edit]

Geronimo married Chee-hash-kish, and they had two children, Chappo and Dohn-say. Then he took another wife, Nana-tha-thtith, with whom he had one child.[71] He later had a wife named Zi-yeh at the same time as another wife, She-gha, one named Shtsha-she and later a wife named Ih-tedda. Geronimo's ninth and last wife was Azul.[72]

The great-great-grandson of Geronimo, Harlyn Geronimo, taught Apache language lessons at Mescalero Apache Reservation until his death in 2020.[73]

Religion[edit]

Geronimo was raised with the traditional religion of the Bedonkohe. When questioned about his opinions concerning life after death, he wrote in his 1905 autobiography:

As to the future state, the teachings of our tribe were not specific, that is, we had no definite idea of our relations and surroundings in after life. We believed that there is a life after this one, but no one ever told me as to what part of man lived after death ... We held that the discharge of one's duty would make his future life more pleasant, but whether that future life was worse than this life or better, we did not know, and no one was able to tell us. We hoped that in the future life, family and tribal relations would be resumed. In a way we believed this, but we did not know it.[74]: 178

In his later years Geronimo endorsed Christianity and stated:

Since my life as a prisoner has begun, I have heard the teachings of the white man's religion, and in many respects believe it to be better than the religion of my fathers ... Believing that in a wise way it is good to go to church, and that associating with Christians would improve my character, I have adopted the Christian religion. I believe that the church has helped me much during the short time I have been a member. I am not ashamed to be a Christian, and I am glad to know that the President of the United States is a Christian, for without the help of the Almighty I do not think he could rightly judge in ruling so many people. I have advised all of my people who are not Christians, to study that religion, because it seems to me the best religion in enabling one to live right.[74]: 181

He joined the Dutch Reformed Church in 1903 but four years later was expelled for gambling.[74]: 181 To the end of his life, he seemed to harbor ambivalent religious feelings, telling the Christian missionaries at a summer camp meeting in 1908 that he wanted to start over, while at the same time telling his tribesmen that he held to the old Apache religion.[75]

Alleged theft of Geronimo's skull[edit]

Six members of the Yale secret society Skull and Bones, including Prescott Bush, served as Army volunteers at Fort Sill during World War I.[76] In 1986, former San Carlos Apache chairman Ned Anderson received an anonymous letter with a photograph and a copy of a log book claiming that Skull and Bones held the skull of Geronimo. He met with Skull and Bones officials about the rumor. In 2006, Marc Wortman discovered a 1918 letter from Skull and Bones member Winter Mead to F. Trubee Davison that claimed the theft:[77] The group's attorney, Endicott P. Davidson, denied that the group held the skull and said that the 1918 ledger saying otherwise was a hoax.[78] The group offered Anderson a glass case containing what appeared to be the skull of a child, but Anderson refused it:[79]

The skull of the worthy Geronimo the Terrible, exhumed from its tomb at Fort Sill by your club ... is now safe inside the tomb, and bone together with his well worn femurs, bit and saddle horn.

— [77]

The second "tomb" refers to the building of Yale University's Skull and Bones society. But Mead was not at Fort Sill, and Cameron University history professor David H. Miller notes that Geronimo's grave was unmarked at the time.[77] The revelation led Harlyn Geronimo to write to President George W. Bush (the grandson of Prescott Bush) requesting his help in returning the remains:

According to our traditions the remains of this sort, especially in this state when the grave was desecrated ... need to be reburied with the proper rituals ... to return the dignity and let his spirits rest in peace.

— [80]

In 2009, Ramsey Clark filed a lawsuit on behalf of people claiming descent from Geronimo, against several parties including Robert Gates and Skull and Bones, asking for the return of Geronimo's bones.[78] An article in The New York Times states that Clark "acknowledged he had no hard proof that the story was true."[81] Investigators, including Bush family biographer Kitty Kelley and the pseudonymous Cecil Adams, say the story is untrue.[82][83] A military spokesman from Fort Sill told Adams, "There is no evidence to indicate the bones are anywhere but in the grave site."[82] Jeff Houser, chairman of the Fort Sill Apache tribe of Oklahoma, calls the story a hoax.[79] In 1928, the Army covered Geronimo's grave with concrete and provided a stone monument, making any possible examination of remains difficult.[81]

Military usage[edit]

Paratroopers[edit]

Inspired by the 1939 film Geronimo, U.S. Army paratroopers testing the practice of parachuting from planes began a tradition of shouting "Geronimo!" to show they had no fear of jumping out of an airplane. Other Native American-based traditions were also adopted in WWII, such as "Mohawk" haircuts, face paint, and sporting spears on their unit patches. The paratrooper unit 1/509th PIR at Fort Johnson, LA, uses Geronimo as their moniker.[84]

Code name[edit]

The United States military used the code name "Geronimo" for the raid that killed Al-Qaeda terrorist Osama bin Laden in 2011, but its use outraged some Native Americans.[85] It was subsequently reported to be named or renamed "Operation Neptune Spear".[86][87]

Harlyn Geronimo, known to be Geronimo's great-grandson, said to the Senate Commission on Indian Affairs:[88]

[The use of "Geronimo" in the raid that killed Bin Laden] either was an outrageous insult [or] mistake and it is clear from the military records released that the name Geronimo was used at times by military personnel involved for both the military operation and for Osama Bin Laden himself.

Commemorations[edit]

Three towns in the U.S. are named after Geronimo: one each in Arizona, Oklahoma, and Texas. Also named after him was the SS Geronimo, a WWII Liberty ship. In the U.S. Postal Service's serial "Legends of the West", a 29¢ postage stamp showing Geronimo was issued on October 18, 1994.[89]

In popular culture[edit]

Music[edit]

Geronimo is a track recorded by Les Elgart and his orchestra on their Sophisticated Swing album (Columbia CL-536; 1953).[90] The British instrumental rock group The Shadows released a single “Geronimo” in 1963, written by group member Hank Marvin. It stalled at number 11 in the British charts, their lowest since breaking through in 1960 with the charttopping Apache. In 1972, Michael Martin Murphey's song Geronimo's Cadillac was inspired by Walter Ferguson's photo of Geronimo sitting in a luxury Locomobile. The song hit number 37 on the Billboard Hot 100, and it was later covered by Cher and Hoyt Axton. The German duo Modern Talking released a different song with the same title (but with a less explicit lyrical connection to Geronimo) in 1986.[91][92] In 2014, the indie pop band Sheppard released Geronimo, which reached number one on the Australian Singles Chart in April that year.[93] In 2019 the American Red-Dirt Country band Shane Smith and the Saints, released in 2015, their second studio album Geronimo[94] was released on Geronimo West Records. This album has the title track Geronimo.

Film[edit]

Geronimo has been featured in many western movies; for example, in John Ford's Stagecoach (1939), it is Geronimo's band that chases the stagecoach across Monument Valley.[95] There are four films in which he is the title character. In Geronimo! (also 1939), directed by Paul Sloane, he is played by Chief Thundercloud but only in a supporting role as the film is essentially about the U.S. Army's attempts to capture him. However, in the similarly-titled Geronimo! (1962), directed by Arnold Laven, Geronimo as played by Chuck Connors is the main character.[96]

In 1993, two films about Geronimo were released within a few days of each other. Geronimo: An American Legend is about his arrest, and he is played by Native American actor Wes Studi. The biopic Geronimo has a wider scope, and he is played by Native American actor Joseph Runningfox.[97]

Television and radio[edit]

On June 29, 1938, a fictionalized Geronimo appeared in a radio episode of The Lone Ranger, titled "Three Against Geronimo". In the episode, Tonto acts as a spy to discover Geronimo's plan to take Fort Custer under a false flag of peace. Tonto strips Geronimo of his concealed knife before the Lone Ranger and a cavalryman named Peterson lure Geronimo's troops into the emptied fort one at a time.

In the TV series "Stories of the Century" the episode "Geronimo" was aired on February 14, 1954. Geronimo was the title of episode 21 of the ABC western series Tombstone Territory. The episode was first broadcast on March 5, 1958, with John Doucette playing the part of Geronimo.[98] Geronimo, played by Enrique Lucero, features prominently in the 1979 miniseries Mr. Horn, starring David Carradine as Tom Horn.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Geronimo (1996). Barrett, S. M.; Turner, Frederick W. (eds.). Geronimo: his own story. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-452-01155-7. Archived from the original on January 5, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 152, 153.

- ^ Debo 1996, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d Utley 2012, pp. 1, 2.

- ^ Debo 1996, p. 268.

- ^ "Apache Indians Southwest". Archived from the original on October 7, 2006.

- ^ Hermann, Spring (1997). Geronimo: Apache freedom fighter. Enslow Publishers. p. 26. ISBN 0-89490-864-2. Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ Debo 1996, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Utley 2012, p. 130.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 1, 130.

- ^ Utley 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Utley 2012, p. 140.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Utley 2012, p. 2.

- ^ Adams, Alexander B. (1990). Geronimo: a Biography. Da Capo Press. p. 391. ISBN 978-0-306-80394-9.

- ^ Haugen, Brenda (2005). Geronimo: Apache Warrior. Capstone. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-0756518455. Archived from the original on September 15, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Geronimo His own story". American History – From Revolution to Reconstruction and what happened afterwards. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ Debo 1996, p. 34.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Utley 2012, p. 27.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 27, 28.

- ^ Debo 1996, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Sweeney, Edwin R. (1986). Sonnichsen, Charles Leland (ed.). Geronimo and the End of the Apache Wars. University of Nebraska Press. p. 36. ISBN 0803291981. Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ a b Barrett, S. M., ed. (1915) [1909]. "In Prison and on the war path". Geronimo's Story of His Life. New York: Duffield & Company. Archived from the original on December 11, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ Debo 1996, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Barrett, S. M., ed. (1915) [1909]. "Coming of the White Men". Geronimo's story of his life. New York: Duffield & Company. Archived from the original on December 24, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Barrett, S. M., ed. (1915) [1909]. "Heavy Fighting". Geronimo's story of his life. New York: Duffield & Company. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ "FILM; Geronimo, Still With a Few Rough Edges Archived February 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine." The New York Times. December 5, 1993

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 96, 108.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 1, 2, 96.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 92–97.

- ^ Debo 1996, p. 117.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 104–112.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 149–159.

- ^ Debo 1996, pp. 236, 237.

- ^ a b Utley 2012, p. 160.

- ^ a b Utley 2012, p. 133.

- ^ Utley 2012, p. 136.

- ^ Utley 2012, p. 135.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 130, 179, 200.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 178, 179.

- ^ a b Hurst, James. "Geronimo's surrender – Skeleton Canyon, 1886". Archived from the original on August 26, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ "Geronimo at Work". Library of Congress, Chronicling America. Daily Tombstone epitaph., April 16, 1886, Image 3. April 16, 1886. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Mary "Mollie" E. Fly (1847–1925)". Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Vaughan, Thomas (1989). "C.S. Fly Pioneer Photojournalist". The Journal of Arizona History. 30 (3) (Autumn, 1989 ed.): 303–318. JSTOR 41695766.

- ^ a b c d Capps, Benjamin (1975). The Great Chiefs. Time-Life Education. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-316-84785-8.

- ^ Herring, Hal (2008). Famous Firearms of the Old West: From Wild Bill Hickok's Colt Revolvers to Geronimo's Winchester, Twelve Guns That Shaped Our History. TwoDot. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-7627-4508-1.

- ^ My Life: The Autobiography of Geronimo. Fireship Press. 2010. ISBN 978-1-935585-25-1. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ National Geographic Vol 182 1992

- ^ a b c "The American Experience, We Shall Remain: Geronimo". PBS. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Haley, James L. (1997). Apaches: a history and culture portrait. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 381. ISBN 0-8061-2978-6. Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Gulf Islands National Seashore – The Apache (U.S. National Park Service)". nps.gov. Archived from the original on September 5, 2010. Retrieved May 24, 2009.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 214–220.

- ^ Debo 1996, pp. 295, 296, 298.

- ^ a b c d e f King, Gilbert (November 9, 2012). "Geronimo's Appeal to Theodore Roosevelt". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on October 31, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

Held captive far longer than his surrender agreement called for, the Apache warrior made his case directly to the president

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 221–254.

- ^ Debo 1996, p. 372.

- ^ Debo 1996, pp. 374, 376.

- ^ In Geronimo's Footsteps by Corine Sombrun & Haiyln Geronimo, Skyhorse publishing, Inc., 2014

- ^ Utley 2012, p. 256.

- ^ Tom (June 20, 2014). "Geronimo Participates in Roosevelt's Inaugural Parade". Ghosts of DC. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Debo 1996, p. 421.

- ^ Utley 2012, pp. 254–259.

- ^ Delgado, Juan Carlos. "Gerónimo hablaba español". No. August 23, 2009. ABC. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ Barrett, Stephen Melvil and Turner, Frederick W. (1970), Introduction, Geronimo: His Own Story: The Autobiography of a Great Patriot Warrior, Dutton, New York, ISBN 0-525-11308-8 ;

- ^ Barrett, S. M., ed. (1915) [1909]. "At the World's Fair". Geronimo's story of his life. New York: Duffield & Company. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ "Death of Geronimo, History Today". Historytoday.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ "American Experience We Shall Remain: Geronimo" (PDF). PBS. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 4, 2013.

- ^ "Google maps location". Google Maps. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ "Wives and burial place of Geronimo". Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2009.

- ^ Gatewood, Charles B. (2009). Louis Kraft (ed.). Lt. Charles Gatewood & His Apache Wars Memoir. University of Nebraska Press. p. xxxiii.

His ninth wife was Azul (1850–1934), a Chokonen who had been captured by Mexicans early in her life. She did not marry Geronimo until the Apache prisoners of war moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma Territory (probably 1907). She remained with him until his death in 1909 and never remarried.

- ^ "Mescalero Apache Tribe Performs Blessing Ceremony at White Sands Missile Range". www.army.mil. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c Geronimo (1971). Barrett, S. M. (ed.). Geronimo, His Own Story. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-349-10260-0. LCCN 72-113457.

- ^ Debo 1996, pp. 437–438.

- ^ Reitz, Stephanie (February 18, 2009). "Geronimo's kin sue Skull and Bones over remains". Huffington Post. Hartford, Connecticut. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c Lassila, Kathrin Day; Branch, Mark Alden (May–June 2006). "Whose Skull and Bones?". Yale Alumni Magazine. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Daniels, Bruce (February 27, 2009). "Geronimo Lawsuit Sparks Family Feud". Albuquerque Journal. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Pember, Mary Annette (July 9, 2007). "Tomb Raiders". Diverse Issues in Higher Education. Archived from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ Buncombe, Andrew (June 1, 2006). "Geronimo's family call on Bush to help return his skeleton". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on October 26, 2006. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- ^ a b McKinley Jr., James C. (February 19, 2009). "Geronimo's Heirs Sue Secret Yale Society Over His Skull". www.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Adams, Cecil (November 11, 2005). "Is Geronimo's skull residing at Yale's Skull and Bones? Was it stolen from the grave by Prescott Bush?". The Straight Dope. Archived from the original on April 16, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ^ Kelley, Kitty (2004). The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty. Doubleday. pp. 17–20. ISBN 0-385-50324-5.

- ^ Anderson, Chuck. "Geronimo yell of World War II paratroopers". B-westerns.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Osama Bin Laden: Why Geronimo?". BBC News. May 3, 2011. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (May 4, 2011). "US Official: "This Was a Kill Mission"". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ America, Good Morning (May 3, 2011). "A defense official tells ABC News the mission to take Osama Bin Laden was called Operation Neptune Spear". Archived from the original on February 8, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ Berestein Rojas, Leslie (May 6, 2011). "'An unpardonable slander:' The controversy over the use of 'Geronimo' in bin Laden operation". Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "American Indian Subjects on United States Postage Stamps". US Postal Service. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ^ "Les Elgart". Cupertino, California: Apple Inc. June 1990. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ Clements, William M. (2013). Imagining Geronimo: An Apache Icon in Popular Culture. Albuquerque: UNM Press. pp. 198ff. ISBN 978-08-26353-22-1. Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ DeGagne, Mike. "Michael Martin Murphey Geronimo's Cadillac". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 12, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Byron, Tim (April 17, 2014). "Number Ones: Sheppard Geronimo". Vine Music. Sydney: Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on April 20, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ "The Official Shane Smith & The Saints Website". The Official Shane Smith & the Saints Website. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ Newman 1990, p. 53.

- ^ Newman 1990, p. 67.

- ^ Carter, Kevin (December 19, 1993). "Yelling Geronimo!". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Tombstone Territory – Season 1 Episodes". TV Guide. Indian Land, South Carolina: Red Ventures. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

Bibliography[edit]

- Debo, Angie (1996). Geronimo, The Man, His Time, His Place. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-08-06118-28-4.

- Geronimo (1971). Barrett, Stephen Melvil; Turner, Frederick W. (eds.). Geronimo: His Own Story. The Autobiography of a Great Patriot Warrior. New York City: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-04-52011-55-7.

- Newman, Kim (1990). Wild West Movies. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-07-47507-47-5.

- Utley, Robert M. (2012). Geronimo. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-03-00198-36-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Bigelow, John Lt. On the Bloody Trail of Geronimo New York: Tower Books, 1958.

- Brands, H.W. The Last Campaign: Sherman, Geronimo and the War for America Doubleday, 2022.

- Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1970.

- Carter, Forrest. Watch for Me on the Mountain. Delta. 1990. – Also published as Cry Geronimo.

- Davis, Britton. "The Truth about Geronimo" New Haven: Yale University Press, 1929.

- Faulk, Odie B. The Geronimo Campaign. Oxford University Press: New York, 1969.

- Killblane, Richard E. "Arizona Tiger Hunt", Wild West, December 1993.

- Killblane, Richard E. "Geronimo's Final Surrender", Wild West, February 1994.

- Opler, Morris E. & French, David H. Myths and tales of the Chiricahua Apache Indians. [1941] Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

- Reilly, Edward. "Geronimo: The Warrior", Public Domain Review, 2011.

External links[edit]

- Works by Geronimo at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Biography of Geronimo hosted by the Indigenous People Portal

- Geronimo at Indians.org

- "Obituary: Old Apache Chief Geronimo Is Dead". The New York Times. Lawton, Oklahoma. February 18, 1909. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- Adams, Guy. Who Was Geronimo, and Why is There Controversy Over His Remains?, The Independent, June 23, 2009

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Geronimo (Apache leader)

- Germonimo: The Warrior article by Edward Rielly on the personal tragedy which underpinned Geronimo's warrior life.

- Geronimo

- 1829 births

- 1909 deaths

- 19th-century Native American leaders

- 20th-century Native Americans

- Apache Wars

- Chiricahua people

- Converts to Protestantism from pagan religions

- Deaths from pneumonia in Oklahoma

- History of Mexico

- Native American Christians

- Native American people of the Indian Wars

- Native Americans imprisoned at Fort Marion

- People from Graham County, Arizona

- People from New Mexico

- People of the American Old West

- Reformed Church in America members

- Prisoners who died in United States military detention