America May Have Too Many College Graduates

There's no question that, in today's economy, you are better off with a college education than you are without one. The unemployment rate for grads is lower, and their wages are higher, as are their chances of advancing to a management job.

But does that necessarily mean the whole economy would be better off if more Americans had a diploma? That's a tougher issue, one which has been the subject of some lively debate since the Georgetown Center On Education the Workforce published a study last week examining how workers at different education levels have fared in the job market.

Count me among the skeptical. The jobs climate for bachelor's holders still isn't stellar, many are taking positions they're probably overqualified for, and there aren't any obvious signs that employers are struggling to find educated employees. Speaking broadly, it seems there are already more college grads in United States than can fit into our cramped economy.*

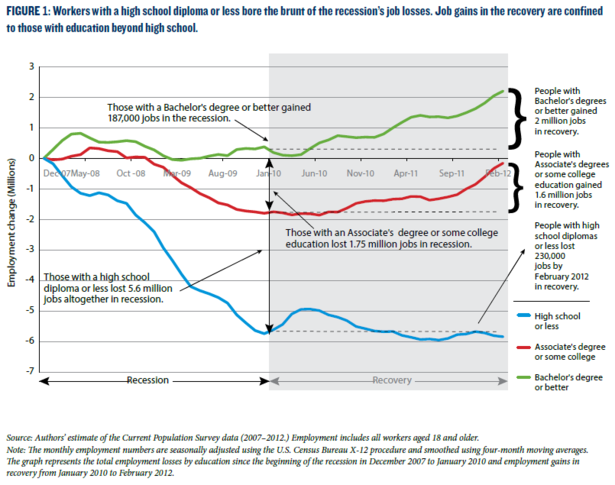

Again, college-educated Americans do have it better than most. As the Georgetown report illustrated, workers with a bachelor's degree or higher added more than 2 million jobs between December 2007 and February of this year. Meanwhile, the market for high school grads is still stuck in a trench, having barely budged since late 2009.

But not all college grads have it equally rosy. As the Washington Post's Dylan Matthews has pointed out, the Georgetown report misleadingly sandwiches together plain-old bachelor's holders with workers who have a master's, doctorate, or professional degree. And according to data Matthews cites from the Economic Policy Institute, between 2007 and 2011, 98.3 percent of the job gains in that combined group went to the advanced degree holders. These days, it seems we're really in a grad school economy.

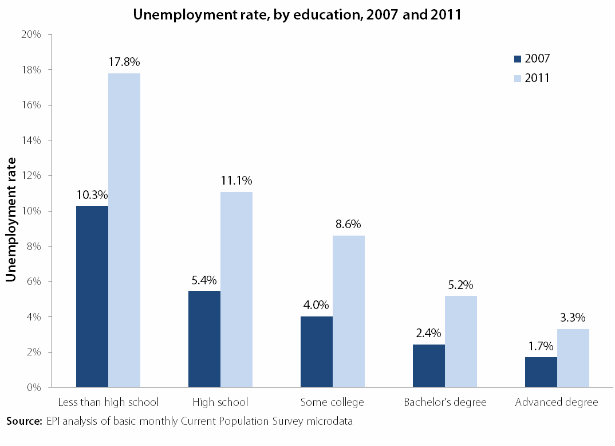

That reality plays out pretty clearly in the unemployment figures, as shown in this chart posted by EPI's Lawrence Mishel. Bachelor's holders, like everyone else, have suffered from much worse joblessness than normal during the recovery. Today, they're still facing 4.1 percent unemployment, well above pre-recession levels. If there was a great shortage of college talent in the labor market, it's reasonable to assume their situation would have improved faster.

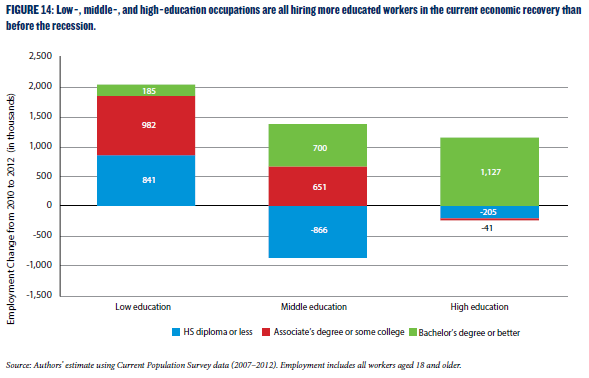

But it's not just an issue of whether college grads are finding work; it's the kind of work some of them are getting that's problematic. As shown in this next graph from the Georgetown report, since the recession began, employers have hired more than 700,000 bachelor's holders into what are usually considered middle-education occupations -- jobs where only half to three-quarters of employees have at least some college. Think dental hygienists, cops, and travel agents. Another 185,000 are in low-education positions. Think McDonald's or your neighborhood coffee shop.

To be fair, those numbers aren't quite as ominous as they sound. Many of these jobs are simply more sophisticated than they used to be and therefore require increasingly educated employees. Manufacturing workers need to operate more advanced, computer-operated machinery. Sales agents have to understand technology they're pitching to prospective buyers. Hospitals want more nurses with bachelor's. In a report last year, the Georgetown Center referred to that evolution as "upskilling."

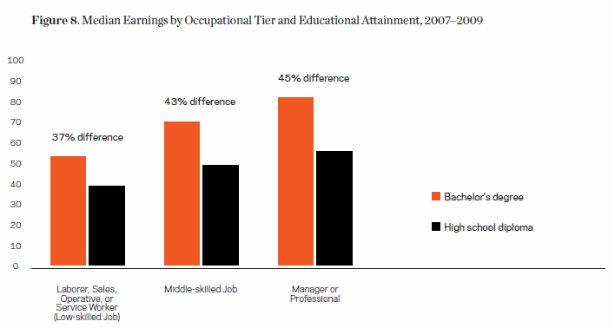

Usually, when a college graduate goes to work in traditionally low-skill field, they end up earning a good deal than their coworkers without diplomas. Take police officers. Per the Georgetown study:

[A] police officer is considered a middleskill job, but officers with a Bachelor's degree earn 30 percent more than those with just a high school diploma. Much of this gap is related to more employees with Bachelor's degrees working in higher-paying jobs on the police force, such as detectives or supervisors. Another example is a self-employed plumber or other craftsperson who earns more than many college graduates.

In 2009, bachelor's holders in mid-skill occupations make a 43 percent wage premium.

So we're not necessarily looking at an entire generation of underpaid, overqualified barristas. But upskilling can't explain all of the migration of college grads away from traditionally white collar occupations. For instance, according to Georgetown, around 300,000 bachelor's holders have been hired to work in "office and administrative support services." In other words, they're taking jobs as secretaries and clerks. It's hard to see that as anything other than the result of a desperately lousy job market. And it means less educated workers are probably being displaced.

None of this, though, answers for sure whether we have too many or too few college graduates for the economy. And the Georgetown Center says firmly that we have too few. They reached that conclusion in their 2011 report by using the college wage premium -- how much more bachelor's holders make compared to everyone else -- to try and model the changing demand for college graduates over time. Then they look at the actual number of young people getting degrees. As of 2010, demand was far outstripping supply.

But something seems intuitively off about their findings. The college wage premium has essentially been frozen for a decade, even as earnings for high school grads have actually fallen. If there was such intense competition for college-educated talent, you'd expect it to continue rising.

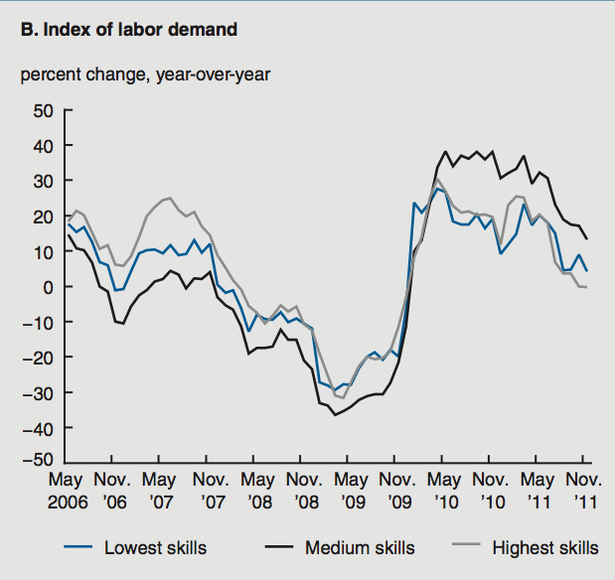

For another view, we can turn to the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, which released a study in June on the so-called "skills shortage" many believe is afflicting the economy. This is the idea that there are jobs out there, but workers just don't have the education they need to get them. In the end, they found the evidence for such a mismatch was "mixed." As the graph below shows, which is based off of actual hiring data, the demand for low-, medium-, and high-skill labor has all been moving more or less in tandem. The slight exception is in the medium-skill market, which could be a sign of the "upskilling" trend. But there's really no obvious proof that employers have are scrambling over each other for educated labor.

As I wrote above, the evidence as to whether we have too many or too few college grads isn't conclusive. Chances are, we're not generating an entire wave of over-educated espresso artists. And there are also almost certainly specific job sectors of the economy, such as engineering, suffering from a dearth of talent. But college graduates are still facing some of the worst employment prospects they've had in years. There may simply be more of them than our limp current economy can use.