Zhou Liangjun was pumped. For nearly a year, he watched as the Shanghai Stock Index soared. The young marketing executive had never trusted China's stock market, but now something appeared to have changed. The government seemed to encourage investment in equities, particularly as the country's housing slump intensified. So early last month, he took half of his savings and plunked it into stocks on the Shanghai exchange.

His timing couldn't have been worse. Though China's market is still up 30 percent year-on-year, it's experienced a dramatic descent this summer. In 10 trading days ending on June 26, the market lost a fifth of its value. Two years ago, Zhou bought a flat and has seen its value decline modestly. Now the equity market is further eating into his net worth, leaving him shell-shocked and wondering what to do with what's left of his savings. "Maybe I should invest abroad," he says. Maybe I can buy a house in the U.S. Maybe I should buy stocks there, too. I don't know."

For Chinese citizens, and investors across the globe, that's the trillion-dollar question. Households in China have 8.8 trillion renminbi, the equivalent of $1.4 trillion, in savings. And once they start investing abroad, as Zhou is considering, the impact on global markets—everything from real estate to stocks and bonds—will be huge.

To a degree, it already is. Though the bulk of Chinese household savings is stuck in that country ($50,000 is officially the most a Chinese passport holder is allowed to send abroad each year), in practice, the situation is murky. Wealthy and even upper-middle-class Chinese have ways to ship money out of the country. There are middlemen, for example, who demand hefty fees—up to 20 percent—to help Chinese savers move money abroad.

Increasingly, people are willing to pay. Before the rout in the stock market began, China saw a slump in the domestic real estate market—by far the most favored investment for middle- and upper-class Chinese. Property and stocks are the most common ways Chinese tend to save, given that banks offer interest rates on savings that continue to linger around the inflation rate. Over a year ago, the government started to support the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets—by allowing more trading on margin, among other things. But Chinese investors have also been looking to foreign property markets to stash their money, and the current market turmoil at home will only intensify that interest. According to the National Association of Realtors in the United States, the Chinese just became the largest foreign purchasers of residential property in the United States, accounting for 16 percent of all foreign purchases in the quarter ending March 31, compared with 14 percent purchased by Canadians, traditionally the top foreign investor in U.S. residential property.

Given the constraints on individuals moving money out of China, that's a remarkable development. And because China is gradually easing those restrictions, the dollar figures will likely increase. Beijing is preparing to launch a pilot program later this year that would allow individuals in six of the country's wealthiest cities to invest in stocks, bonds and property abroad. The program comes as the government is trying to crack down on the gray market that helps funnel individual wealth overseas. But the politics of going after individuals evading the $50,000 annual limit is tricky. For years, politically connected families—the rulers of the Communist party and their relatives, known as "princelings"—have been able to move money across borders with impunity. The rules that apply to ordinary Chinese haven't applied to them, and it's unclear if Beijing will continue to look the other way.

Further policy changes are also afoot. The chief of China's central bank, Zhou Xiaochuan, said the government's ultimate goal is to make the renminbi fully convertible. And in May, a researcher at the People's Bank of China wrote that the central bank aims to make that happen by the end of 2015. While the timing is still uncertain, David Wong, chief economist at Shui On Development Ltd., a big Shanghai-based property developer, tells Newsweek he expects full capital account liberalization "in two years."

That's an ambitious timetable, and it carries risks. If domestic real estate stalls, at best, and the equity market gyrates, investing abroad will seem all the more enticing. With so much money in household savings, significant Chinese investment overseas could set off a financial exodus—one that could destabilize the country's own economy.

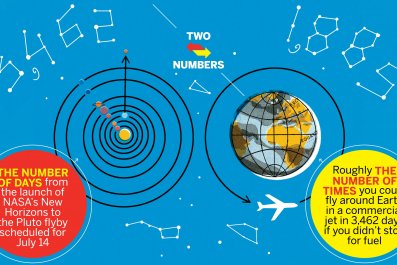

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has issued warnings along those lines. It says the rapid liberalization of capital flow into and out of China could produce net outflow equal to as much as 15 percent of the country's GDP, or roughly $1.35 trillion. "We wouldn't advise doing this in one step," Markus Rodlauer, the IMF's China mission chief, told The Wall Street Journal earlier this year. We'd advise continuing with a gradual approach."

A massive number of households investing abroad is only one part of a potential surge of Chinese money moving overseas. Chinese companies—both state-owned and private—are more aggressively pursuing foreign investment projects, which have been dominated by energy and natural resource deals. That's about to change in a major way, as Chinese firms try to diversify their foreign holdings.

When middle-class individuals like Zhou bid for a house or an apartment in San Francisco, Sydney or London, few locals tend to get upset. Homeowners generally like it when the value of their properties rise. Yet a surge in Chinese corporate investment abroad will likely be controversial. In the 1990s, Japanese purchases of U.S. assets—from movie studios to high profile real estate—created a firestorm. Reciprocity—they can buy us, but we can't buy them—was a huge issue. It will be a far bigger issue as China gets into the same game, because entire sectors of Beijing's economy, dominated by state-owned companies, are off-limits to foreign investors. A recent report by the Rhodium Group, a New York–based consultancy, and Berlin's Mercator Institute for China Studies says Chinese foreign direct investment is going to grow from $6.4 trillion in assets to $20 trillion by 2020. If that's true, it will likely elicit an unprecedented backlash across the globe.

If that happens, China will say it is simply taking the next logical step in its ongoing integration into the world economy. But the country's critics, whose numbers are growing, will say Beijing is intent on domination, not integration.