Jacob L. Shapiro

Yesterday marked 15 years since Sept. 11, 2001. Since then, the U.S. and other forces have waged almost constant war in the Middle East, the birthplace of Islam and civilization itself. On Sept. 11, we pause and remember where we were that day and what we were thinking. That is altogether appropriate. However, it is also appropriate to consider how the map of the Middle East has changed since 9/11. Maps are useful tools, but they can be dangerous because they lock patterns into your mind that may not be accurate. The only way to counter this is to force yourself to look at things from a different perspective. To do this, we have created two maps of the Middle East: one of the region on Sept. 11, 2001 and another of the region on Sept. 11, 2016.

Osama bin Laden had one great goal in mind for al-Qaida, and it wasn’t simply to kill Americans. For bin Laden, attacks like 9/11 were a means to an end. Bin Laden really sought to transform the Islamic world from within by insurrection. He came from a wealthy Saudi family, and when he looked at this map, he saw sclerotic regimes, indulgent dictators and a society in a general state of collapse. The once-proud heirs of the Prophet Muhammed’s revelation had been turned into pawns in the Cold War and had imbibed foreign ideals – first nationalism, then socialism, then petty authoritarianism. And now they were weak and ignorant of their own traditions, and bin Laden hoped to change this.

Al-Qaida didn’t have the power to do this single handedly. And so al-Qaida attacked the United States, hoping to create a rallying cry in the Muslim world not just against the West but against the Western-sympathizing dictators who had steered the Arab Muslim world to this disastrous place. In total, 2,977 people died on 9/11 – but from al-Qaida’s point of view, 9/11 was initially a failure. The U.S. punished Afghanistan and the Taliban, but Afghanistan was on the periphery of al-Qaida’s fight. Al-Qaida hoped to draw the U.S. into the heart of the Middle East, and at first the U.S. didn’t take the bait.

But 9/11 also showed that bin Laden understood something the U.S. and others did not. And that was that most Middle Eastern states were in fact weak, their borders artificial. The 9/11 attacks may not have immediately set off the chain reaction bin Laden hoped for, but his diagnosis of the situation proved to be accurate. Eventually, the tinder ignited, sparked by the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the U.S. attempt to install a liberal democracy in Baghdad. Since then, because of war, popular unrest (most notably the 2011 so-called Arab Spring), economic frailty and various other dynamics, the map of the Middle East has changed dramatically.

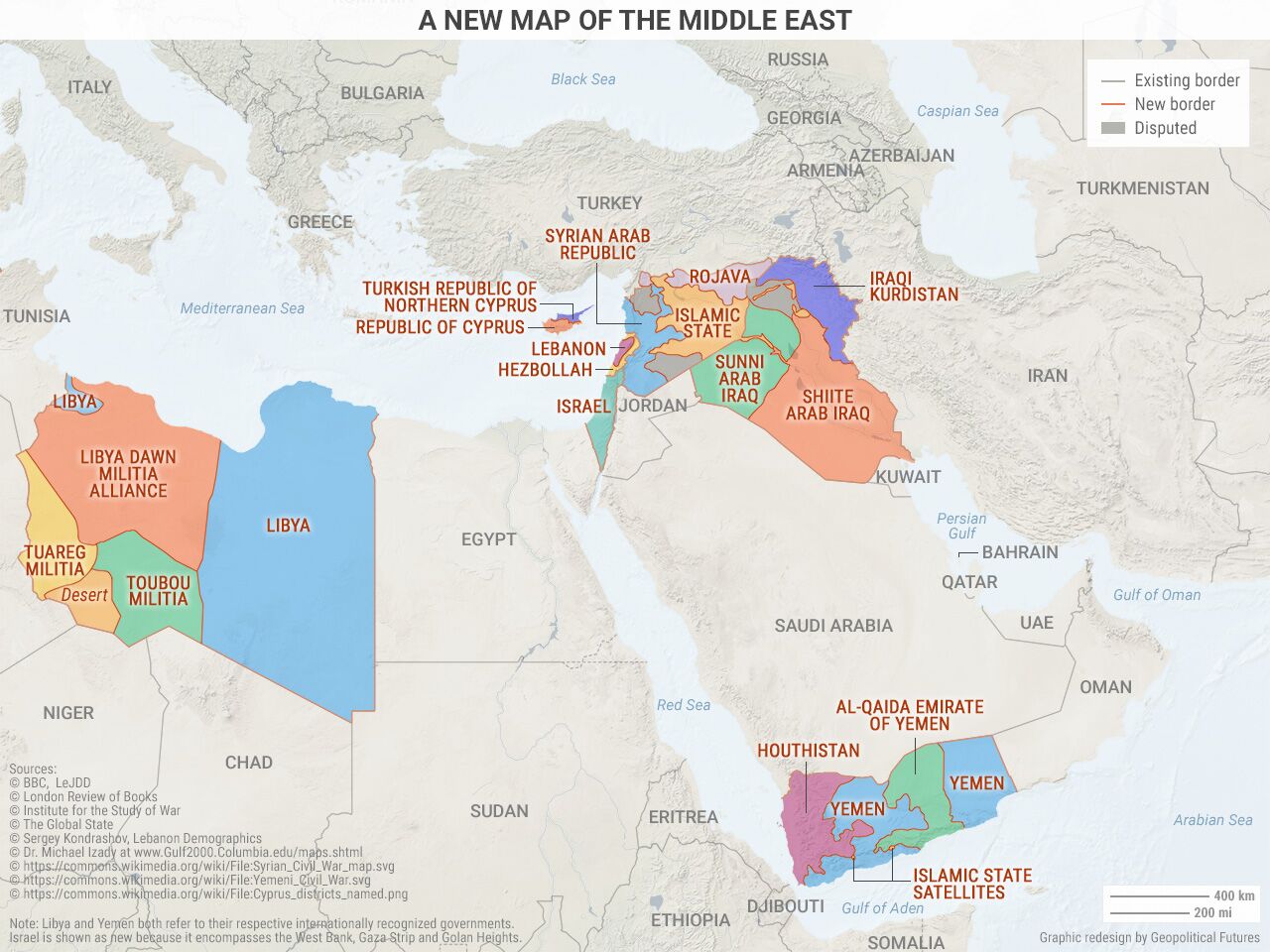

This is a map of the Middle East on Sept. 11, 2016. The map does not show official political borders. It shows the forces that exert power over certain territory. It is a very different map than the first and represents the realization of at least some of bin Laden’s objectives.

Libya, for instance, is no longer a country. The old Libya was the 16th largest country in the world by area but only had a population of 6 million split between two population centers – Tripoli and Benghazi. The distance between Tripoli and Benghazi is over 600 miles, which is mostly desert. The hinterlands support small populations of various tribal groups and the Tuareg, many of whom now exert control over regions and battle each other for position and territory.

Yemen has fallen apart again, with fresh civil war kicking off in 2014, a few years after Arab Spring protests shook the country. The Saudis and their allies support what is still recognized internationally as Yemen. The Houthis and their supporters have a stronghold in the north. Al-Qaida has found enough space to operate its own little fiefdom in the country, and the Islamic State is there too. It is the perfect example of jihadist groups taking advantage of popular disillusionment with the old order of things.

Lebanon remains as it has been since the 1960s: hopelessly divided and deadlocked. Only now, Hezbollah has become both a political party and a fifth-column military force in the small Levantine country. Hezbollah has in recent years traded the occasional skirmish with Israel for supporting Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian Arab Republic, but remains dominant in stretches of land that is for all intents and purposes Hezbollah’s sovereign territory.

Egypt looks relatively stable despite its unrest and the 2013 coup d’état, but Egypt is under significant strain. The economy is in shambles, its military is dealing with an insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula and other jihadist terrorist threats at home, and its 80 million plus people live in an area roughly the size of the state of Kentucky, clustered on either bank of the Nile River.

Jordan is under similar strain – the fact that Jordan has been able to hold together amid the chaos surrounding it is a minor miracle. Almost 20 percent of the people living in Jordan are Syrian refugees.

Syria and Iraq have been destroyed and will not recover, at least not in their previous form. At the heart of this is the Islamic State, a splinter of al-Qaida, which took advantage of both the power vacuum in Iraq after the U.S. invasion and the sectarian rivalries embedded within the region. Bin Laden hoped to begin the process of building a caliphate by overthrowing Middle Eastern dictators. The Islamic State is building that caliphate by conquering territory and ruling it and has thus far met with success beyond what could have been imagined for such a group in 2001.

Syria has splintered into at least three different segments. First is the Islamic State. Second is the small, partially disconnected statelet the Syrian Kurds have carved out for themselves, which they call Rojava, on the Jazira Plain. Third is the remnants of the Syrian Arab Republic led by Assad’s regime – exactly the type of regime Bin Laden hoped al-Qaida would help break apart. Assad’s regime is a shadow of its former self, though it has solidified control over the Alawite coast as well as most of Syria’s major metropolitan areas: Homs, Hama and Damascus.

Iraq has split into at least four different segments. The Islamic State is under severe pressure there but remains a formidable force. Iraq’s Kurds in the north enjoy autonomy through the Kurdistan Regional Government – independence is a fait accompli at this point. Shiite Arab Iraq oscillates between being an Iranian vassal state and attempting to assert its own writ. Sunni Arab Iraqis, with the least physical control over their territory than any other entity on this map, remain something of a wildcard. IS could not have grown into what it is today without them, but that tacit support has waned in the last year.

Sitting atop this chaotic situation are the Middle East’s four regional powers: Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Israel. This map reveals that these countries face grave challenges and potential opportunities. Turkey must fear spillover from the chaos raging to the south, the result of both Syria’s civil war and the rise of the Islamic State – but that also means Turkey has a chance to reclaim its influence in some of the old Ottoman territories. Iran has to deal with Sunni Arabs, the Islamic State and the Kurds, all claiming land within territory that used to belong to its mortal enemy. These are all threats – but they also present a chance for Iran to gain a base of operations in the heart of the Middle East from which it can project power.

Saudi Arabia, a vast, oil-rich desert whose economy is under severe strain, faces a war on two fronts, and there are limits to the amount of treasure it can use to protect itself. Israel is surrounded by general chaos, but its two most important strategic partnerships – with Egypt and Jordan – remain in place. Israel’s would-be enemies are also too fractured and too busy fighting each other to give Israel a hard time. Despite the unease Israel feels looking at this map, ironically Israel is more secure today than at any other point in its modern history. As for the Palestinians, they have never been more divided, and Israeli military and economic dominance of the Palestinian territories is at this point a simple, if controversial, fact.

Looking at the old map of the Middle East is like traveling back in time. It is an echo of a past long gone. Comparing that old map to the new reveals the thinking of those who live there and gives a sense of the direction in which events have developed since 9/11. It’s not how bin Laden drew it up or planned it, but 15 years after 9/11, the map looks a lot more like he would have wanted, despite a massive expenditure of American (and Russian, French and various other foreign) resources in the region to stop those very developments. Bin Laden had a deep understanding of his part of the world in 2001. Looking at these maps bears that out – and points towards an inexorable conclusion: These new borders will change too, and that will necessitate more new maps.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President