In the 1800s it was the Luddites smashing weaving machines. These days retail staff worry about automatic checkouts. Sooner or later taxi drivers will be fretting over self-driving cars.

The battle between man and machines goes back centuries. Are they taking our jobs? Or are they merely easing our workload?

A study by economists at the consultancy Deloitte seeks to shed new light on the relationship between jobs and the rise of technology by trawling through census data for England and Wales going back to 1871.

Their conclusion is unremittingly cheerful: rather than destroying jobs, technology has been a “great job-creating machine”. Findings by Deloitte such as a fourfold rise in bar staff since the 1950s or a surge in the number of hairdressers this century suggest to the authors that technology has increased spending power, therefore creating new demand and new jobs.

Their study, shortlisted for the Society of Business Economists’ Rybczynski prize, argues that the debate has been skewed towards the job-destroying effects of technological change, which are more easily observed than than its creative aspects.

Going back over past jobs figures paints a more balanced picture, say authors Ian Stewart, Debapratim De and Alex Cole.

“The dominant trend is of contracting employment in agriculture and manufacturing being more than offset by rapid growth in the caring, creative, technology and business services sectors,” they write.

“Machines will take on more repetitive and laborious tasks, but seem no closer to eliminating the need for human labour than at any time in the last 150 years.”

Here are the study’s main findings:

Hard, dangerous and dull jobs have declined

In some sectors, technology has quite clearly cost jobs, but Stewart and his colleagues question whether they are really jobs we would want to hold on to. Technology directly substitutes human muscle power and, in so doing, raises productivity and shrinks employment.

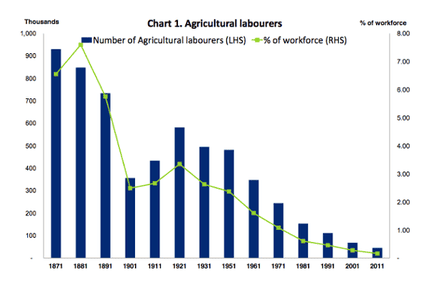

“In the UK the first sector to feel this effect on any scale was agriculture,” says the study.

In 1871, 6.6% of the workforce of England and Wales were classified as agricultural labourers. Today that has fallen to 0.2%, a 95% decline in numbers.

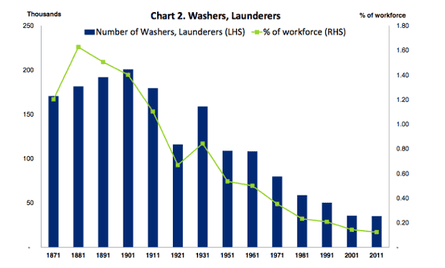

The census data also provide an insight into the impact on jobs in a once-large, but now almost forgotten, sector. In 1901, in a population in England and Wales of 32.5 million, 200,000 people were engaged in washing clothes. By 2011, with a population of 56.1 million just 35,000 people worked in the sector.

“A collision of technologies, indoor plumbing, electricity and the affordable automatic washing machine have all but put paid to large laundries and the drudgery of hand-washing,” says the report.

‘Caring’ jobs have risen

The report cites a “profound shift”, with labour switching from its historic role, as a source of raw power, to the care, education and provision of services to others.

It found a 909% rise in nursing auxiliaries and assistants over the last two decades. Analysis of the UK Labour Force Survey from the Office for National Statistics suggest the number of these workers soared from 29,743 to 300,201 between 1992 and 2014.

In the same period there was also a

- 580% increase in teaching and educational support assistants

- 183% increase in welfare, housing, youth and community workers

- 168% increase in care workers and home carers

On the other hand, there was a

- 79% drop in weavers and knitters from 24,009 to 4,961

- 57% drop in typists

- 50% drop in company secretaries

Technology has boosted jobs in knowledge-intensive sectors

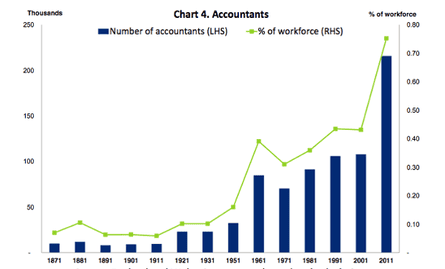

In some sectors – including medicine, education and professional services – technology has raised productivity and employment has risen at the same time, says the report.

“Easy access to information and the accelerating pace of communication have revolutionised most knowledge-based industries,” say the authors. At the same time, rising incomes have raised demand for professional services.

For example, the 1871 census records that there were 9,832 accountants in England and Wales and that has risen twentyfold in the last 140 years to 215,678.

Technology has shifted consumption to more luxuries

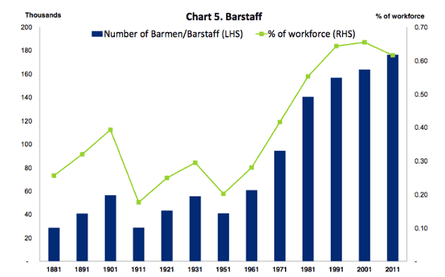

Technological progress has cut the prices of essentials, such as food, and the price of bigger household items such as TVs and kitchen appliances. The real price of cars in the UK has halved in the last 25 years, notes Stewart.

That leaves more money to spend on leisure, and creates new demand and new jobs, perhaps explaining the big rise in bar staff, he adds.

“Despite the decline in the traditional pub, census data shows that the number of people employed in bars rose fourfold between 1951 and 2011,” the report says.

... and left more money for grooming

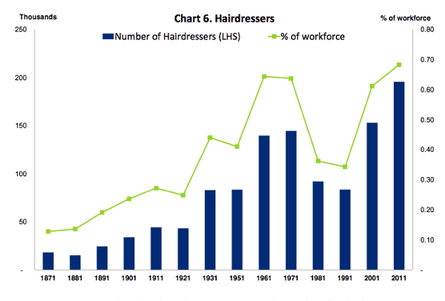

Concluding that “the stock of work in the economy is not fixed”, the report cites the surge in hairdressers as evidence that where one avenue closes in the jobs market, others open.

The Deloitte economists believe that rising incomes have allowed consumers to spend more on personal services, such as grooming. That in turn has driven employment of hairdressers.

So while in 1871, there was one hairdresser or barber for every 1,793 citizens of England and Wales; today there is one for every 287 people.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion